By Gary Aiken | October 3, 2024

Cheryl Crow sang the title song for this month’s insight about a relationship gone wrong. In the lyrics, she desires to love again, but she knows it’s just not meant to be – the first cut is the deepest. Similarly, I think the Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell was singing his heart out at the press conference in September to convince markets that he would cut rates to stave off some unseen and, in our view, low probability recession. Deep down though, the bond market seems to suggest that significantly lower rates just aren’t necessary. The first cut may have been the deepest in a shallow rate-cutting cycle.

The Federal Reserve cut its benchmark rate, the Federal Funds Rate, by 50 basis points (0.5%) to kick off the first rate-cutting cycle in the post-pandemic era. Wall Street economists were split between whether the first cut should be 25 or 50 basis points, with most rather ambivalent. The important part was that the Fed needed to recognize the mounting disparity between the current inflation rate of 2.5% and the overnight policy rate of 5.3%. If allowed to go on for too long, tight monetary policy could certainly weigh on the economy. A cooling job market is evidence of the burden of tight monetary policy. Still, government spending propelled GDP estimates higher during the third quarter.

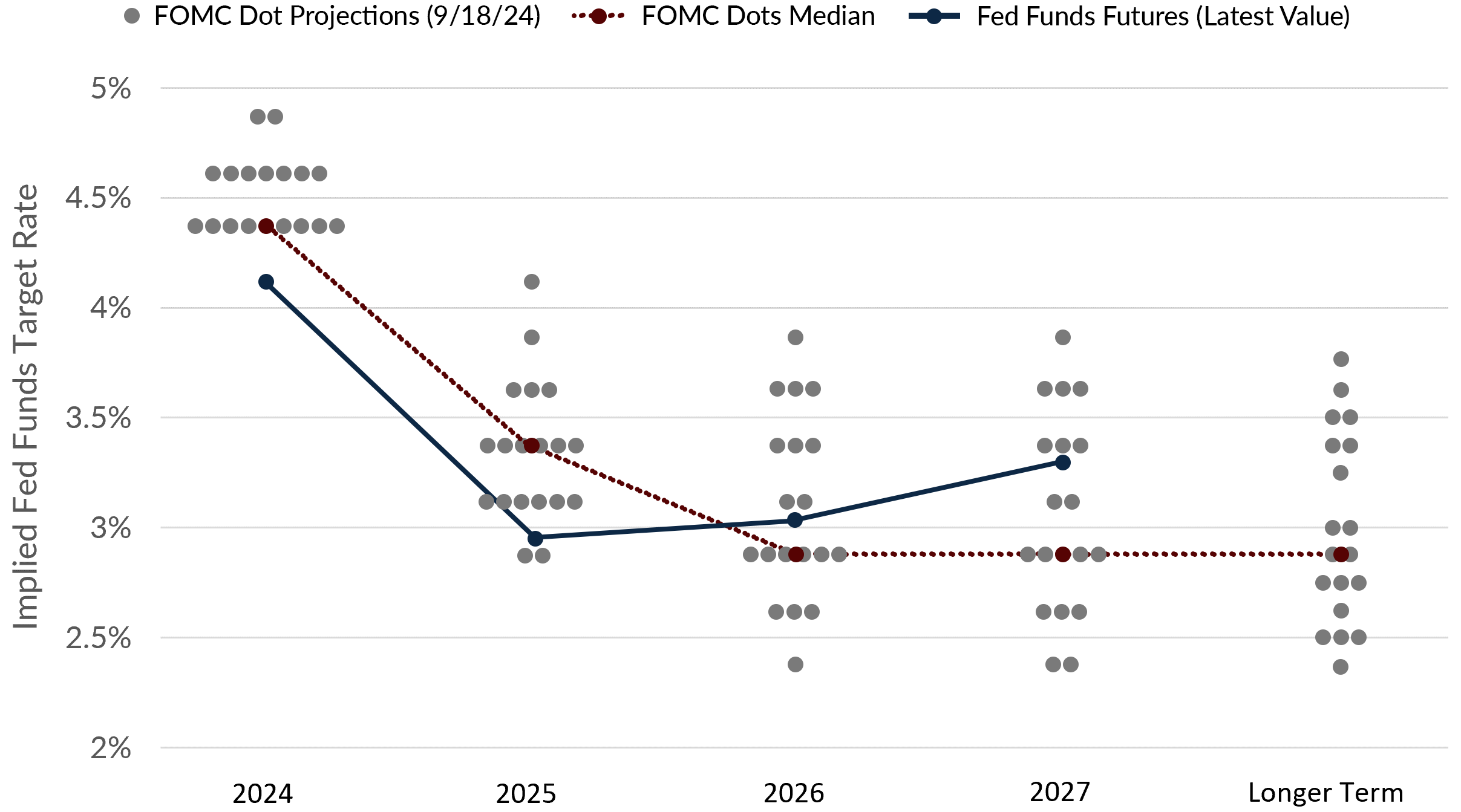

In January, I made a compelling (and correct) argument that the Federal Reserve and market participants have priced in an overly aggressive easing cycle. Federal Reserve Open Market Committee participants estimate where they expect future growth, inflation, and monetary policy to be in the near and distant future. An output called the “dot plot” shows each participant’s view of where they estimate the fed funds rate will be at different points in the future. September’s dots show an aggressive easing cycle again, and I find myself similarly contrarian.

The Fed’s Dot Plot Implies Significantly Lower Interest Rates

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US); Bloomberg Finance, L.P.

There are several reasons why I think that future interest rate cuts may be less than expected. Instead of many 50 basis point cuts, the first cut may have been “the deepest,” and a shorter series of 25 basis point cuts may be the more likely path.

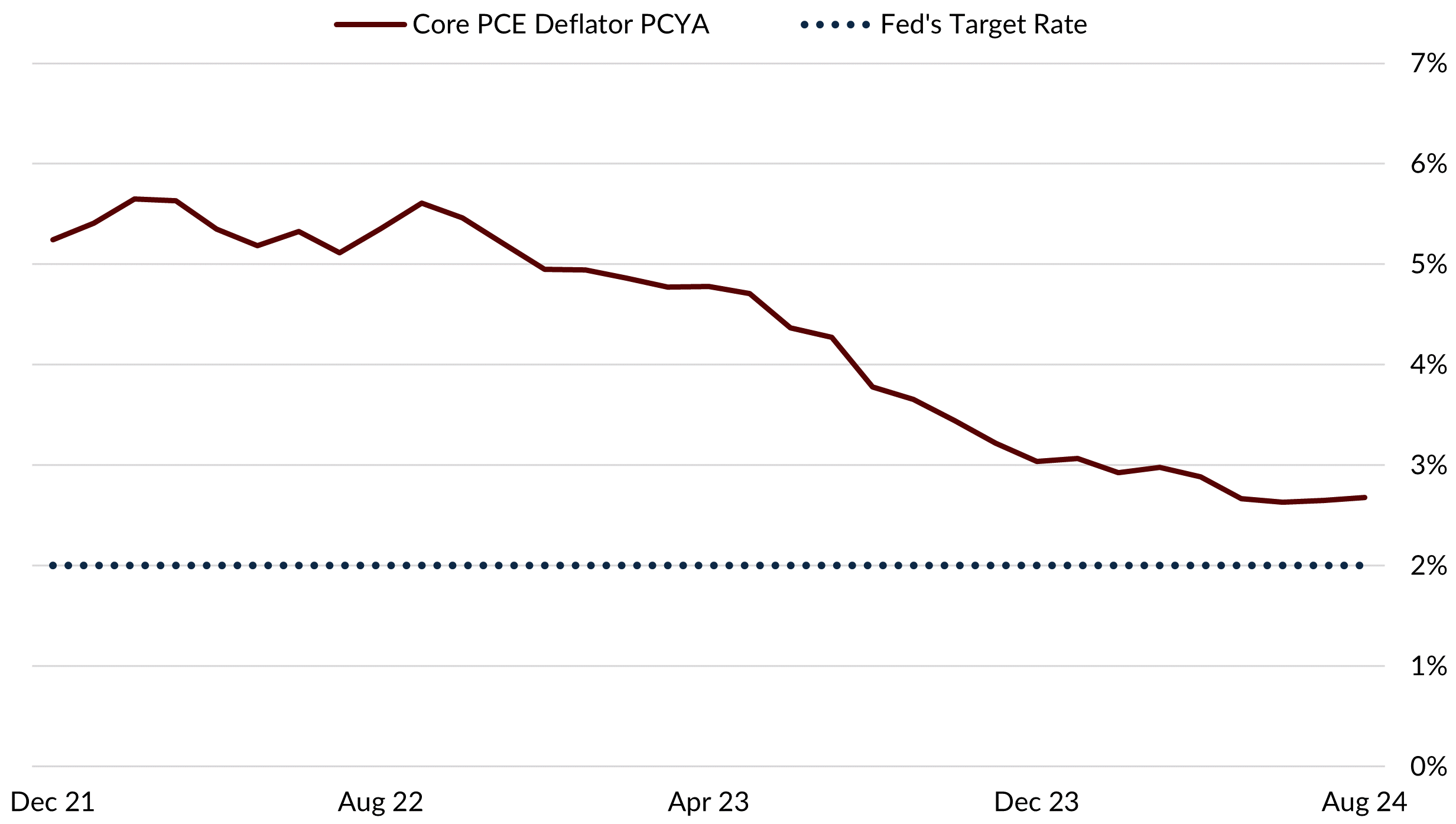

Inflation is slower to come down than expected. The chart below shows year-over-year inflation according to the Fed’s preferred measure, the Core Personal Consumption Expenditures Index (Core PCE). Economist John Silvia highlights that inflation is stabilizing above the Fed’s 2% target. Additionally, the University of Michigan survey reveals that participants anticipate long-term inflation to be around 3.1% over the next 5 to 10 years. This sentiment suggests that inflation expectations are becoming “unanchored” from the Fed’s target. Expectations often have a nasty way of turning into reality.

Inflation: Settling in Above Target

Source: John Silvia, Dynamic Economic Strategy; Bloomberg Finance, L.P.

Inflation expectations and actual inflation above the Fed’s target may curb the Fed’s desire to bring short-term and long-term interest rates down as much as predicted. I often cite a simple mathematical shorthand example. Let’s say we experience real 1 to 2% growth coupled with 2.5% to 3% inflation. That would give a range of 3.5% to 5.5% for the fed funds rate over the medium term. That range’s midpoint of 4.5% is far above the Fed’s 2.9% endpoint in the dot plot.

Despite a tighter job market, wages continue to rise. Unions have pressured managements to raise wages for contracts not negotiated since the great inflation. This presents a continued challenge to the assumption that wages and the prices of goods and services tied to those wages cannot rise faster. The presidential election may result in a tighter immigration policy, and even deportations could send away many job holders, reigniting wage pressure to find workers to perform those vacated jobs. The immigration during the Biden-Harris administration has put strains on parts of the economy but also alleviated worker shortages. Although quantifying the jobs created for temporary foreign workers in the United States has been difficult, wage inflation could return if their temporary status was overturned.

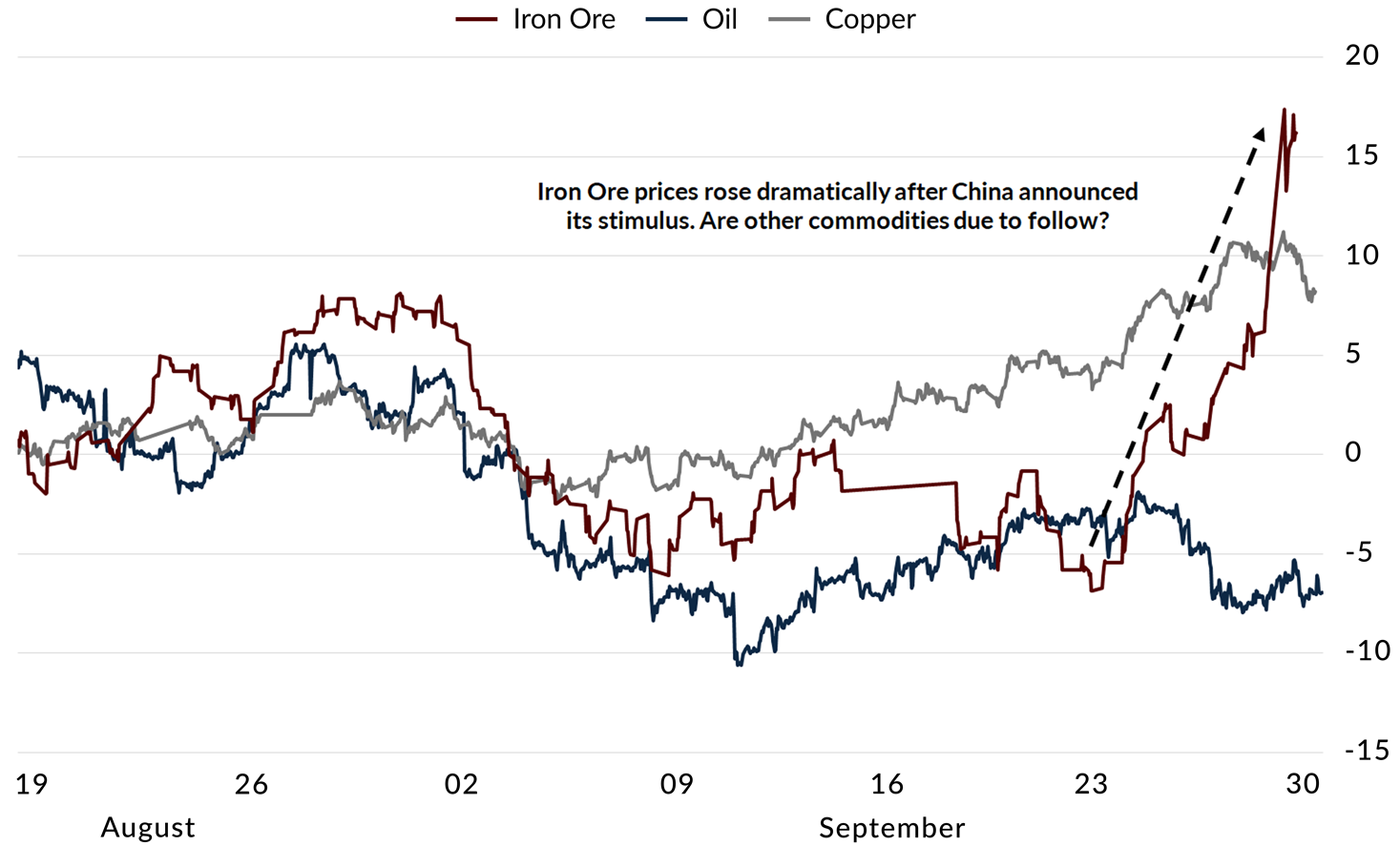

China exports inflation, not deflation this time. From its admittance to the World Trade Organization through the pandemic, China had been a cheap labor and goods supplier to the United States. They also exported deflation that offset some inflation in the United States, keeping our inflation rate at nearly 2% for two decades. The abundance of cheap labor and exported deflation is over. China’s wages are rising, and other countries – e.g., India, Vietnam, etc. – have been saturated by U.S. manufacturing. We may have reached the endpoint for offshoring labor’s deflationary exports. At the same time, China is embarking on an expansionary monetary policy of its own.

Chinese Stimulus Moves Commodity Prices Higher

Source: Bloomberg Finance, L.P.

China is printing Yuan to inflate its economy, which has been suffering from a real estate depression like our 2008-09 crisis. This time, though, if China is successful, it may inflate the prices of oil, copper, and iron ore, and export inflation to the United States. Cheap energy has been a great advantage for the United States, but rising oil and base metal prices could reverse the recent trends that have allowed the Fed to lower interest rates.

While the Federal Reserve may have intentions and forward guidance reasons for suggesting significant cuts, there is good reason to believe that the first cut was the deepest. There may be significant market headwinds to continuing declines in the inflation rate and, therefore, interest rates. Among these are skilled labor wages, immigration-related labor supply issues, and the importation of inflation from China. Still, the most optimistic scenario for the Fed not to lower interest rates as much as expected is my base case: the U.S. economy just doesn’t need significantly lower interest rates to keep growing.

Author

Gary Aiken, Chief Investment Officer

Gary Aiken is the Chief Investment Officer for Concord Asset Management and is responsible for macroeconomic analysis, asset allocation, and security selection, as well as trading and investment operations.

Gary has over 21 years of investment experience and holds an undergraduate degree in economics from the University of Maryland and an MBA from The George Washington University School of Business.

—

Disclosures: Please remember that past performance may not be indicative of future results. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product (including the investments and/or investment strategies recommended or undertaken by Concord Asset Management, or any non-investment related content, made reference to directly or indirectly in this article will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s), be suitable for your portfolio or individual situation, or prove successful. Due to various factors, including changing market conditions and/or applicable laws, the content may no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions. Moreover, you should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this article serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from Concord Asset Management. To the extent that a reader has any questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to his/her individual situation, he/she is encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of his/her choosing. Concord Asset Management is neither a law firm, nor a certified public accounting firm, and no portion of this content should be construed as legal or accounting advice. A copy of Concord Asset Management’ current written disclosure Brochure discussing our advisory services and fees is available upon request or at https://concordassetmgmt.com/. Please Note: If you are a Concord Asset Management or Concord Wealth Partners client, please remember to contact the firm in writing, if there are any changes in your personal/financial situation or investment objectives for the purpose of reviewing, evaluating, and/or revising our previous recommendations and/or services, or if you would like to impose, add, or to modify any reasonable restrictions to our investment advisory services. Concord Asset Management and Concord Wealth Partners shall continue to rely on the accuracy of information that you have provided. Please Note: If you are a Concord Asset Management or Concord Wealth Partners client, please advise us if you have not been receiving account statements (at least quarterly) from the account custodian.